Your Brain Lies About Danger

Human brain ignores statistics and asks one question instead: "Can I remember this happening?"

In a single day of 2001, about 3000 Americans died in terrorist attacks.

If you're old enough, you remember where you were when you've seen the news. If you're not old enough, you've seen the footage. Everyone's seen the footage.

Where were you when you found out that 1.2 million people died in car accidents that same year?

You weren't anywhere. Because no one told you. Just one crash, then another, then another. About 3000 deaths per day. Every day. The entire year.

Both of these are real numbers. Real people. But only one of them reshaped the entire world politics. Wars. New departments. Trillions of dollars.

The other one? Exposed to nothing. People just... kept dying. Every year. Still do. Probably right now, somewhere, someone is dying in a car.

Why does one number feel like an emergency and the other feels like weather?

Question about letter K

The word "heuristic" comes from the Greek heuriskein. To find. To discover. It's the same root that gave us "Eureka" – what Archimedes supposedly shouted in his bathtub.

A heuristic is a shortcut. A way for your brain to find an answer without doing much of the math.

In 1973, two psychologists named Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman asked people a simple question: Are there more English words that start with the letter K, or more words with K as the third letter?

Most people confidently said starting with K.

They were wrong. Words with K in the third position – like "ask" or "cake" – outnumber them about two to one.

But when you try to think of K words, how do you search? You go to the K section of your mental dictionary. You search by first letter. That's how we organize language in our heads. Words starting with K are just... easier to find.

The brain does something sneaky. It confuses "easy to find" with "must be common".

Tversky and Kahneman called this the availability heuristic. We estimate how likely something is by asking one question: How quickly can I think of an example?

Have a quick example? = must happen all the time.

Can't think of one? = probably rare.

Which would be fine. Except the things that come to mind easily aren't a random sample of reality. They're a very specific sample. The vivid stuff. The recent stuff. The scary stuff.

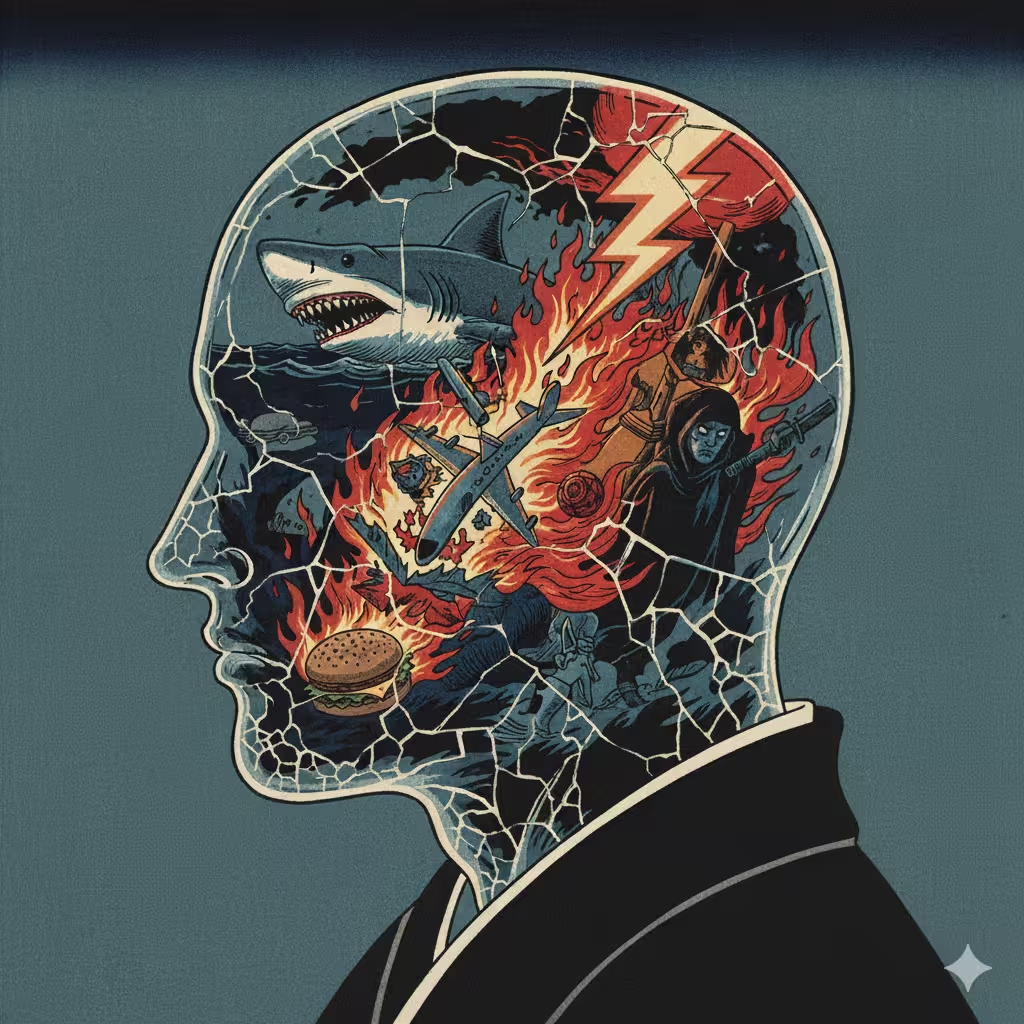

Look at the factors of rememberness:

Notice what's at the bottom.

Actual frequency? How often something actually happens in the world? Brain barely checks.

Sharks vs. furniture

How many people are killed by sharks each year? Worldwide?

About 10.

How many people are killed by falling furniture? In the US alone?

About 11000.

You are a thousand times more likely to be killed by your dresser than by a shark. But Spielberg didn't make a movie called "RACK." Sharks got signal-boosted by being cinematic.

Now consider what decides whether you see something.

In 1973, when Tversky and Kahneman first described the availability heuristic, memories came from two places. Stuff that happened to you. And whatever was in the morning paper.

A newspaper is edited by humans.

An Instagram feed is edited by... not humans?

By AI.

And AI is edited by humans. All of humans and billions of their daily clicks.

AI learned, through trial and error, what makes people click. It doesn't know if something is true or if it matters. It knows you liked, shared and commented.

And what makes people click? Emotional intensity. Vividness. Threat. Outrage.

The exact inputs that trigger the availability heuristic.

Inputs

Change the inputs. Give people the real numbers. Teach base rates and [] in the 4th grade.

Problem solved?

A Nobel Prize winned Daniel Kahneman spent fifty years studying cognitive biases and writing bestselling books. And near the end of his life, he admitted something:

He was still bad at this.

Knowing how the bias works didn't fix it. You can read every word of "Thinking, Fast and Slow." You can board an airplane knowing – consciously, statistically, factually – that flying is safer than driving to the airport.

Your palms can still sweat during turbulence.

Because you don't have one brain. You have something like two. One can do statistics. The other one is older. Much older. It learned, a long time ago, that things which feel dangerous usually are. It doesn't read books. It doesn't care about your Nobel Prize.

And it runs faster.

How much faster? The amygdala – the part that processes fear – responds in about 12 milliseconds. Conscious reasoning takes around 500. By the time you think about whether you're afraid, you already are.

How to outrun 12 milliseconds

Nohow.

But you don't have to. It's a feature that worked for a hundred thousand years and then met TV and the internet.

You scared of something. Okay. When did you last hear about it? Yesterday? With vivid footage? That's probably not danger talking. That's availability.

The more cinematic your mental image of a threat, the more suspicious you should be of your own estimate.

Don't try to stop the gut response – you can't, and fighting it just makes it louder. But you can build a habit of checking it against actual numbers. The numbers won't delete the fear – they just sit beside it. A second opinion, from the slow brain, arriving late but still useful.

Topics

More Read

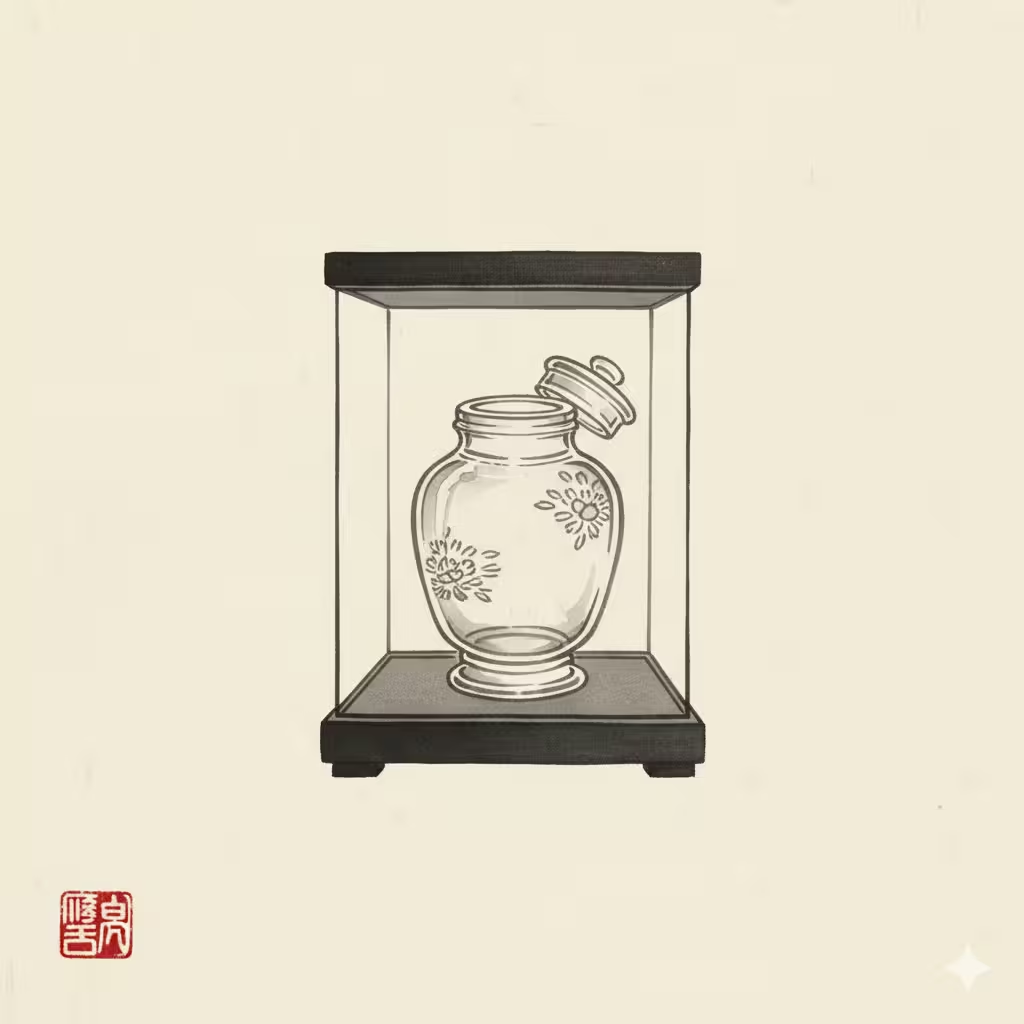

The Inventory Paradox

We treat our values like artifacts in a museum—static, polished, and ready for display. But what if the 'core' you've been excavating is just a collection of empty containers?

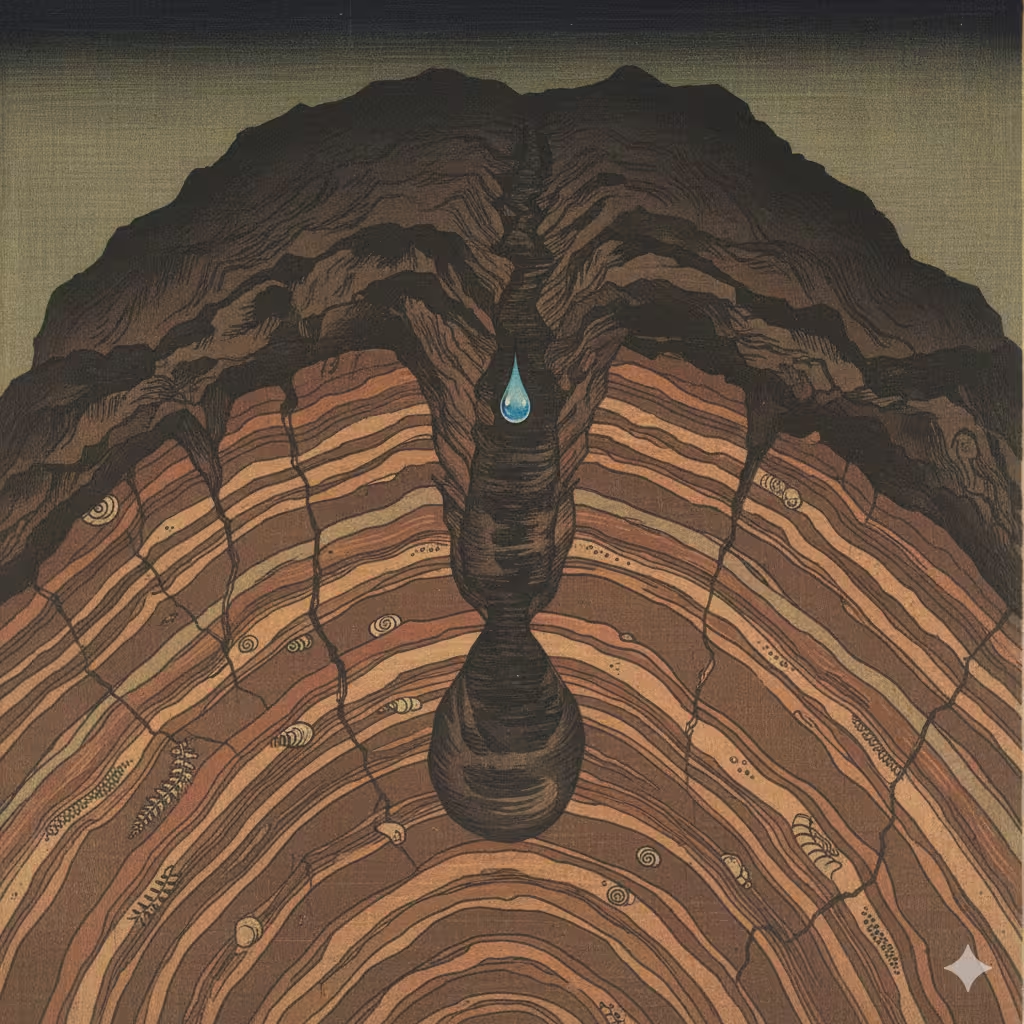

A Boring Secret About Habits

The people who stick with habits aren't more disciplined than you. They've discovered that motivation is a trap, and there's a simpler path hiding in plain sight.

Science Knew Better Way To Study for Over a Century.

Spaced repetition boosts retention by 200-400%. The science has been clear since 1885. Schools still teach cramming. The gap between knowing and doing is a choice.