Other Half of Thinking

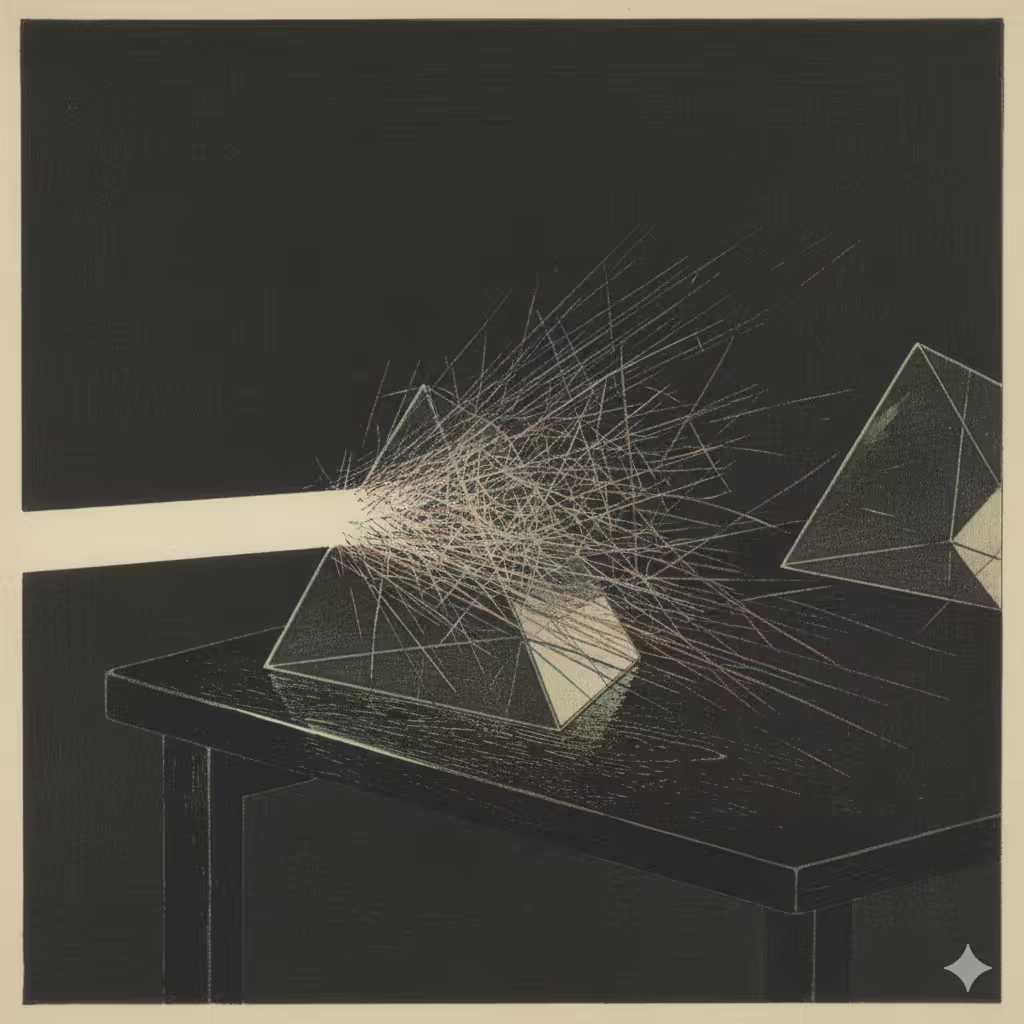

Divergent thinking is only half of creative work. We've built an industry around that half while neglecting everything else that matters.

The word "creativity" is now applied to almost anything that isn't routine. A marketing campaign is creative. A business strategy is creative. A new sandwich at the deli is creative. The word now covers both Beethoven's Ninth Symphony and a novel way of organizing spreadsheets.

This vagueness creates problems. When everything is creative, nothing is. We lose the ability to distinguish between the genuinely new and the merely different, between insight and novelty, between the work that changes how we see things and the work that only rearranges familiar elements.

Linguistics is only a minor part of the deeper problem. Somewhere along the way, creativity became identified with a single cognitive process: the generation of possibilities. Think of many ideas. The more the better. Diverge. Brainstorm. Let the mind roam free.

This is divergent thinking, and it has become the public face of creativity. The psychologist J.P. Guilford introduced the term in the 1950s. It describes thinking that moves outward and generates multiple solutions to open-ended problems instead of converging on a single answer.

Divergent thinking is real and important. But do not equate it to creativity. It is one ingredient in creativity, and not always the hardest one. By mistaking the part for the whole, we have built an entire industry around generating ideas while neglecting the more difficult work of judging, developing, and executing them.

The result is predictable. Organizations overflow with ideas. Brainstorming sessions produce hundreds of sticky notes. Innovation workshops generate excitement and whiteboards full of possibilities. And then almost nothing happens. The ideas pile up, undeveloped, unexecuted, eventually forgotten.

Turns out the problem was never a shortage of ideas.

What Divergent Thinking Is

Guilford identified four components of divergent thinking. Fluency is the ability to generate many ideas quickly. Flexibility is the ability to generate ideas across different categories – not many ideas, but different kinds of ideas. Originality is the ability to generate unusual ideas, responses that others wouldn't produce. Elaboration is the ability to develop ideas in detail, to build them out.

Tests of divergent thinking typically ask open-ended questions. List all the uses you can think of for a brick. How many words can you make from these letters? Draw as many pictures as you can using a circle as a starting point. The tests measure quantity (fluency), variety (flexibility), and unusualness (originality) of responses.

These tests correlate modestly with real-world creative achievement. People who score high on divergent thinking tests are somewhat more likely to produce creative work. "Somewhat", because the correlation is weak – around 0.2 to 0.3 in most studies. Divergent thinking explains about 10% of the variance in creative output.

This is not nothing. But it's far less than the creativity industry implies. The person who can generate many unusual ideas has an advantage, but a small one. Expertise, motivation, judgment, and execution skill matter more.

The tests also reveal something else. Divergent thinking can be trained – also somewhat. Give people practice generating unusual uses for objects, and their fluency and originality scores increase. But the gains don't transfer broadly. You get better at the specific task without necessarily becoming more creative in general. The mind learns the game without changing.

Quick. Different. Unusual. Ideas. Sounds like...

The Brainstorming

In 1948, an advertising executive named Alex Osborn published a book called Your Creative Power. In it, he described a technique his agency used to generate ideas: brainstorming. The rules were simple.

- Gather a group.

- Propose a problem.

- Generate as many ideas as possible.

- Defer judgment – no criticism allowed during the session.

- Build on others' ideas.

- Go for quantity.

The technique spread rapidly. By the 1960s, brainstorming had become standard practice in business. It remains so today. The brainstorming session is the most common ritual of corporate creativity – the meeting where sticky notes appear, voices overlap, and the facilitator writes furiously on a whiteboard.

There is one problem. Brainstorming doesn't always work well.

The research is extensive and consistent. Groups that brainstorm together produce fewer ideas, and fewer good ideas, than the same number of people working alone and pooling their results. Researchers have replicated this finding dozens of times across different settings and populations. It's one of the strongest results in social psychology.

The reasons are not mysterious. Production blocking: only one person can speak at a time, so ideas get lost while waiting for a turn. Social loafing: individuals exert less effort in groups, knowing others will contribute. Evaluation apprehension: despite the "no criticism" rule, people still censor themselves, reluctant to voice ideas that might seem foolish. Anchoring: early ideas shape subsequent thinking, narrowing the range of what gets proposed.

The "no criticism" rule, meant to protect divergent thinking, creates its own problems. Without feedback, bad ideas proliferate alongside good ones. The session ends with a mountain of undifferentiated possibilities, no mechanism for sorting them, and the implicit assumption that quantity alone is valuable.

None of this has slowed the practice. Brainstorming persists because it feels productive. Energy runs high. Participation is visible. Everyone leaves with the sense that something happened. The feeling of creativity substitutes for actual creative output.

Alternatives exist. Brainwriting – where individuals generate ideas in writing before any group discussion – produces better results than traditional brainstorming. Electronic brainstorming, where ideas are submitted anonymously and simultaneously, removes production blocking. The Delphi method structures feedback across multiple rounds. But these alternatives lack the drama of the traditional session. They feel less collaborative, even when they produce more.

The Missing Half

Divergent thinking generates possibilities. But possibilities are cheap. The hard work comes after.

Convergent thinking – the other half that Guilford identified – is the process of evaluating, selecting, and refining. It takes the many ideas and narrows them to the few worth pursuing. It judges which possibilities are good, which are feasible, which align with constraints and goals.

This thinking gets almost no attention in popular discussions of creativity. It's unglamorous. It looks critical criticism, which we're told to defer. It requires saying no to most ideas, which feels negative. It demands expertise to judge quality, which not everyone has.

But convergent thinking is where creative work lives or dies. The great artist is not the one who has the most ideas. It's the one who knows which ideas are worth developing and how to develop them. The successful inventor is not the one who generates the most patents. It's the one who recognizes which inventions will work and marshals resources to build them.

Consider the editing process in writing. The first draft is divergent – getting words on the page, following impulses, allowing mess. The subsequent drafts are convergent – cutting what doesn't work, sharpening what does, making choices about structure and emphasis. Most writers will tell you that editing is where the real work happens. The first draft is necessary but not sufficient. The edited draft is what readers see.

The same pattern holds across many fields. The painter who generates many sketches must select which to develop. The musician who improvises many melodies must judge which deserve a song. The scientist who conceives many hypotheses must determine which are worth testing. The entrepreneur who imagines many businesses must choose which to build.

Divergent without convergent is noise.

A flood of possibilities with no mechanism for selection produces nothing usable. This is the state of a typical organization after their brainstorming sessions: awash in ideas, paralyzed by choice, unable to move forward because everything seems equally plausible.

Why Convergence Is Harder

Divergent thinking asks: what's possible? Convergent thinking asks: what's good?

The second question is harder because it requires judgment, and judgment requires knowledge. To know whether an idea is good, you must understand the domain deeply enough to evaluate quality. The experienced engineer can look at a proposed design and see problems the novice misses. The veteran editor can read a manuscript and identify weaknesses invisible to the amateur.

This is why expertise matters for creativity, despite the romantic myth of the untrained genius. Research consistently shows that creative breakthroughs come from people with deep knowledge of their fields. The outsider who reshapes a domain is vanishingly rare, and usually turns out, on inspection, to be less outside than the myth suggests.

Expertise enables both divergence and convergence. It provides the raw material – the stored patterns and possibilities – from which new combinations emerge. It also provides the judgment to recognize which combinations are valuable. The person who has studied thousands of paintings can see originality that the casual viewer cannot. The person who has analyzed hundreds of businesses can evaluate a new venture with precision the novice lacks.

This creates an uncomfortable truth. Divergent thinking can be faked. Anyone can generate ideas, even good ones. But convergent thinking cannot be faked. You either know enough to judge quality or you don't. The brainstorming session lets everyone participate equally. The evaluation phase exposes who truly understands the domain.

Organizations often avoid this exposure. They extend the brainstorming phase indefinitely, defer judgment perpetually, treat all ideas as equally valid. This feels democratic and inclusive. It also guarantees mediocrity.

Without judgment, there is no quality control. Without quality control, creative output regresses to the mean.

The Conditions That Matter

I want to become a great thinker – what do I need?

Expertise is foundational. Creative people know their domains deeply. They've internalized patterns, techniques, and standards. This knowledge provides both raw material and judgment. You cannot recombine what you don't know. You cannot evaluate what you don't understand.

Creativity requires study. It requires years of learning what others have done. The romantic image of the untaught genius, creating from pure inspiration, is mostly myth. Even apparent exceptions – the outsider artists, the naive inventors – usually reveal extensive self-education on inspection.

Time matters more than we want to admit. Insights emerge after periods of incubation – time away from the problem during which unconscious processing continues. People who step away from a problem and return to it later often solve it more easily than those who persist continuously.

This suggests that the timed brainstorming session may be counterproductive. Forcing idea generation into a scheduled hour works against the mind's natural rhythms. Better to pose the problem, let people think about it over days, and then gather to share. But this is harder to schedule and impossible to observe, so organizations rarely do it.

Constraints promote creativity. This sounds paradoxical but makes sense on reflection. Unconstrained problems are paralyzing – too many directions, no basis for choice. Constraints reduce the search space, focus attention, and force creative solutions within defined limits.

The sonnet form doesn't limit poetry; it shapes it. The budget constraint doesn't prevent innovation; it directs it. The fixed deadline doesn't block creativity; it forces completion. Studies confirm this: moderate constraints increase creative output. Only extreme constraints – so tight that no solution is possible – impede it.

Psychological safety enables the risk-taking that creativity requires. People who fear judgment censor themselves. They propose only safe ideas, avoid unusual combinations, stick close to what's been done before. Creating genuine novelty requires willingness to be wrong, to look foolish, to fail publicly.

This is why the same people often produce more creative work in some environments than others. The organization that punishes failure gets cautious employees. The organization that tolerates intelligent risk-taking gets people willing to try.

Solitude matters, often more than collaboration. Significant work happens alone. The composer alone with the piano. The writer alone with the page. The scientist alone with the data. Groups can contribute at specific stages – providing feedback, identifying problems, spurring new directions – but the core creative work is usually solitary.

This runs counter to the corporate emphasis on collaboration, open offices, and constant meetings. These may have other benefits, but creativity is not among them. The person who never has uninterrupted time to think will struggle to think deeply.

Five simple conditions – why are we here then?

It Starts With Education

Schools face a contradiction regarding creativity. They claim to value it, often listing it among their goals. But their structures systematically suppress it.

The standard classroom rewards convergent thinking. Questions have correct answers. Tests measure whether you've learned what was taught. Grades reward conformity to expectations. The student who gives the expected response succeeds; the student who gives an unexpected one, even if interesting, does not.

Divergent thinking is tolerated in designated creative subjects – art, music, creative writing – and suppressed elsewhere. The math class doesn't reward unusual approaches to problems. The history class doesn't welcome unconventional interpretations. The science class doesn't encourage questioning the textbook.

This is partly practical. Teachers must manage large groups with limited time. Standardized curricula require standardized assessment. But the effect is to train students in convergent thinking while claiming to value creativity. By the time they reach adulthood, most have learned that unusual thinking is risky, expected responses are safe, and creativity is for special occasions only.

Research by Kyung Hee Kim tracked creativity scores in schoolchildren over decades. The trend is downward. Since 1990, scores on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking have declined – most sharply in the elaboration and originality dimensions. Children are becoming less able or less willing to think divergently.

The causes are debated. More standardized testing. More screen time. Less unstructured play. Whatever the cause, the result is concerning. The same society that claims to need innovation is producing young people less capable of it.

Same mistakes are done by adults for adults...

At Workplace

We claim to value creativity but reward conformity. The employee who proposes something genuinely new risks looking foolish, wasting resources, or threatening established interests. The employee who executes standard procedures competently gets promoted.

We hold brainstorming sessions and innovation workshops but lack mechanisms to develop the ideas produced. The sticky notes go into a folder and the folder goes into a drawer. Six months later, no one remembers what was proposed.

We organize for efficiency. Open offices eliminate privacy. Constant meetings eliminate time for deep thought. Metrics emphasize output quantity over output quality. The creative slack that enables genuine innovation looks, to the efficiency-minded manager, wasteful.

We confuse novelty with creativity. The new logo, the redesigned website, the repositioned brand – these are changes, but not necessarily creative achievements. Much of what passes for corporate creativity is reshuffling: new combinations of familiar elements, dictated by fashion instead of insight.

The genuinely creative organization is rare. It

- protects time for uninterrupted thinking.

- tolerates failure in service of learning.

- develops ideas as opposed to merely collecting them.

- rewards substance over performance.

Most organizations cannot sustain this. The pressures toward short-term results, predictability, and efficiency are too strong. Creative work requires patience they don't have, risk they can't tolerate, and judgment they struggle to exercise.

However

None of this is an argument against divergent thinking. It's an argument against mistaking it for the whole of creativity.

Divergent thinking serves real functions. At the start of a project, when the direction is uncertain, generating many possibilities opens options. When a problem seems stuck, deliberately seeking unusual approaches can break the impasse. When expertise narrows vision, forcing divergence can surface overlooked alternatives.

The techniques for supporting divergent thinking work, within limits. Deferring judgment during idea generation does increase fluency. Seeking quantity before quality does produce more options. Deliberately reversing assumptions, making random associations, and applying constraints from other domains can all stimulate unusual ideas.

But these techniques are starting points, not endpoints. The ideas generated must be evaluated, selected, and developed. The one percent that are genuinely good must be identified among the ninety-nine percent that are mediocre or unworkable. And the good ideas must be executed – turned from concepts into reality.

This is where most creative efforts fail. lack of everything that follows divergent thinking.

Bird's-eye View on Process

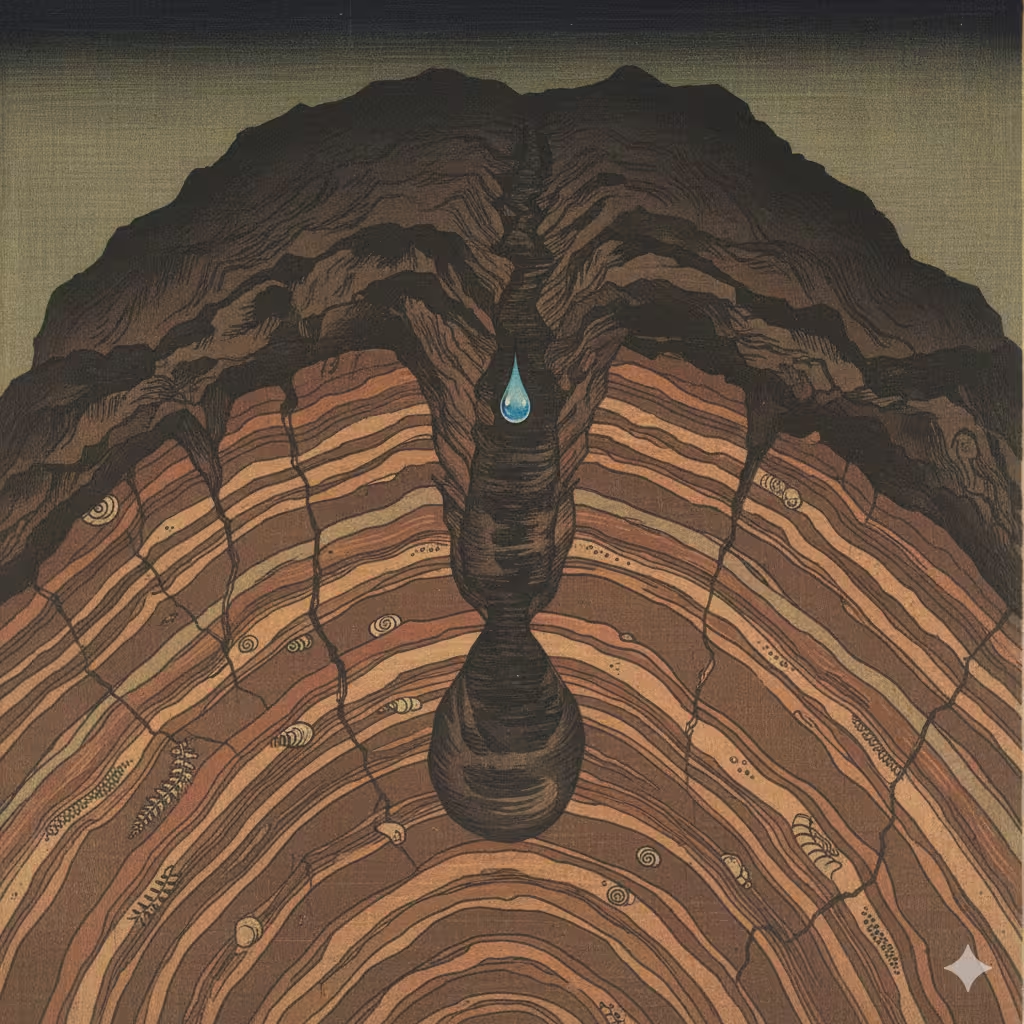

Creativity, understood properly, is a process with stages. Different researchers have named the stages variously, but the structure is similar across accounts.

First, preparation: acquiring knowledge, understanding the problem, absorbing the domain. This is mostly convergent – learning what's already known, building the expertise that enables both generation and judgment.

Second, incubation: stepping away from the problem, allowing unconscious processing to work. This is neither divergent nor convergent but temporal – giving the mind space to make connections outside of conscious attention.

Third, illumination: the emergence of ideas, the flash of insight, the "aha" moment. This is what divergent thinking describes, though it often happens spontaneously without deliberate effort.

Fourth, verification: evaluating, testing, refining. This is convergent – applying judgment to determine whether the idea in fact works, developing it into something complete.

The popular focus on creativity attends almost exclusively to the third stage. Brainstorming and idea generation target illumination. But illumination without preparation produces only noise – connections between things you don't understand. And illumination without verification produces only fantasy – ideas that feel exciting but don't survive contact with reality.

The person who wants to be creative must develop all four capacities. They must study their domain deeply enough to have material to work with. They must allow time for incubation without forcing constant production. They must cultivate the conditions that allow ideas to emerge. They need judgment to pick worthy ideas and skill to complete them.

This is less exciting than the brainstorming session. It takes longer. It requires expertise that cannot be faked. But it's how creative work gets done.

The Individual Path

For the individual seeking to think more creatively, the implications are clear, if demanding.

Study your domain. There is no substitute for knowledge. The creative writer reads voraciously. The creative scientist masters the literature. The creative entrepreneur understands markets, technologies, and human behavior. Divergent thinking without this foundation produces only noise.

Create conditions for incubation. This means not filling every moment with stimulation. Walking, sleeping, showering – the clichéd sites of insight – work because they allow the mind to wander. The person who is always consuming content or responding to messages has no space for unconscious processing.

Practice generating possibilities, but don't stop there. Deliberately seek unusual approaches. Force yourself to list ten ideas, then ten more. Make random associations. Borrow structures from other fields. But then evaluate what you've generated. Identify the one idea worth developing. Pursue it to completion.

Develop your judgment. This is harder than generating ideas but more important. Seek feedback from people who know the domain. Study what works and why. Learn to see quality over novelty. The ability to distinguish good from mediocre, to kill your darlings, to recognize genuinely new ideas – this is what separates creative producers from creative dreamers.

Finish things. Ideas are cheap, execution is expensive. The creative person who starts many projects and finishes none has produced nothing. The discipline to push through the difficult middle stages is necessary. Creativity without completion is only imagination.

The Reconvergence

There is a final twist.

The best creative work often ends in simplicity.

The process may require divergence – exploring many possibilities, pursuing tangents, entertaining absurdities. But the product, if it's good, usually achieves a convergence. The painting that feels inevitable. The solution that seems obvious in retrospect. The insight that, once stated, cannot be unseen.

This is because creative work is communication. The creator has traveled a complex path, but the audience doesn't need to follow every turn. The work must land cleanly, with the clarity that makes complexity look easy.

The divergent phase leaves no trace in successful work. No one sees the discarded drafts, the abandoned approaches, the dead ends. What remains is the path that worked, presented as the only path.

This is the deepest misunderstanding about creativity. The finished product looks convergent – single, unified, clear. The process that produced it through divergence – multiple, scattered, searching approaches. Mistaking the product for the process leads us to imagine that creative people somehow arrive directly at their destinations, skipping the wandering that got them there.

They don't. But the wandering must eventually lead somewhere. Divergent thinking opens the territory. Something else – judgment, skill, persistence – finds the destination within it.

That something else is at least half of creativity. It's the half we've neglected in our enthusiasm for brainstorming sessions and idea generation.

Topics

More Read

Why You Were More Creative at Age 5

Schools claim to value creativity while systematically rewarding its opposite. Workplaces do the same. The data shows the consequences.

A Boring Secret About Habits

The people who stick with habits aren't more disciplined than you. They've discovered that motivation is a trap, and there's a simpler path hiding in plain sight.